In the Studio

”I think a lot of my subject matter is trying to keep a creative outlook and finding the magic in life throughout my day. Life is mysterious, and I want to keep a curious mind.

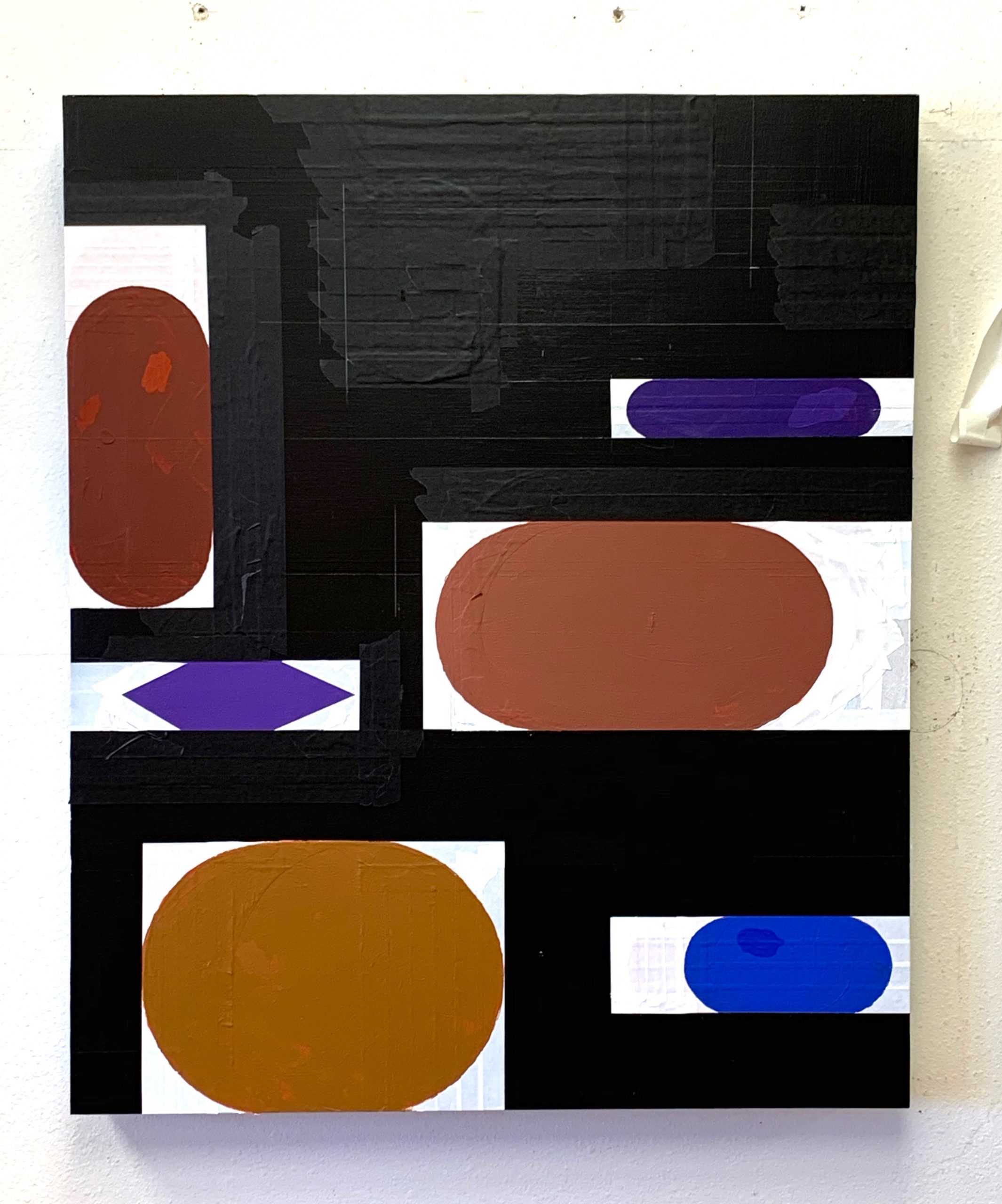

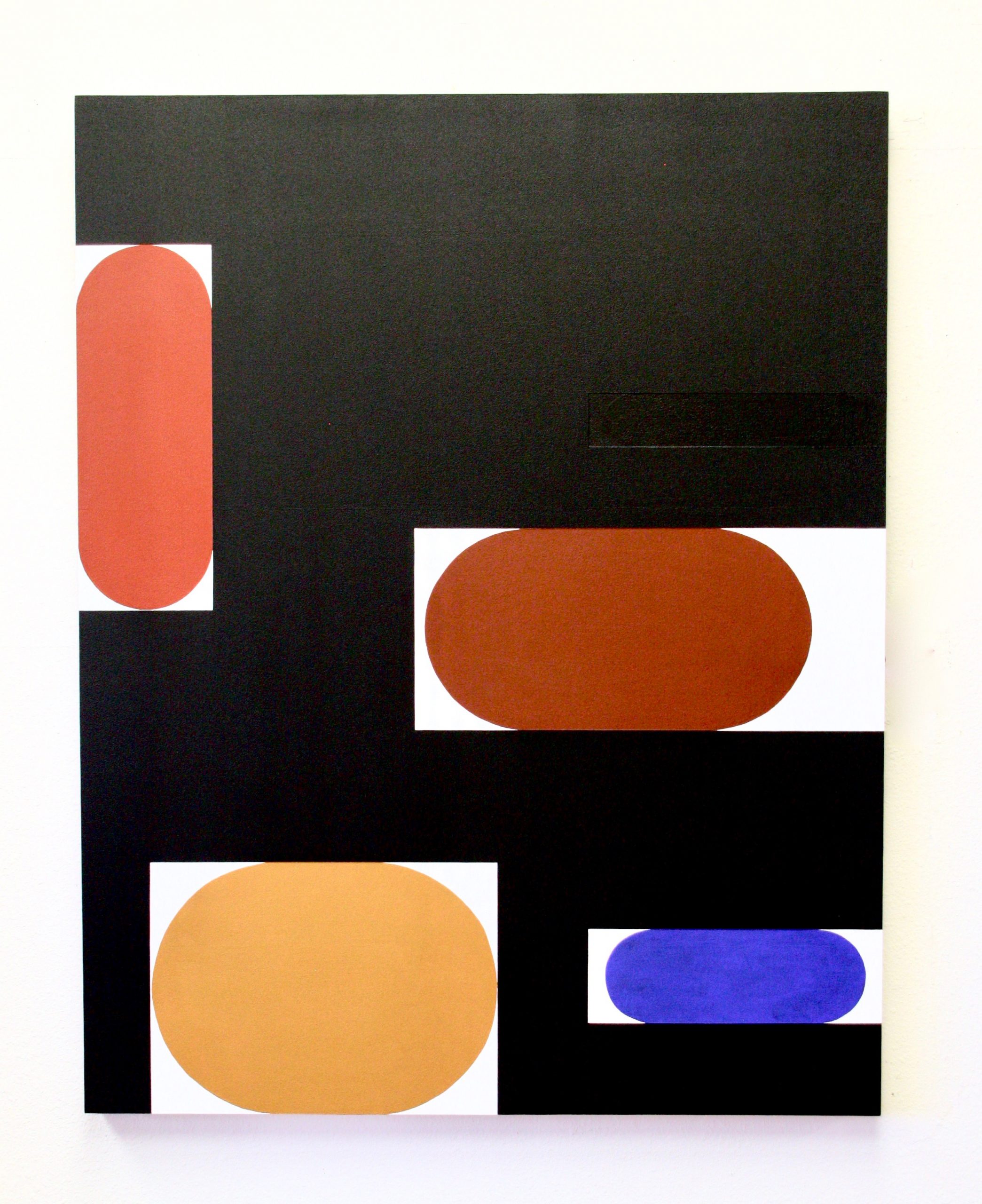

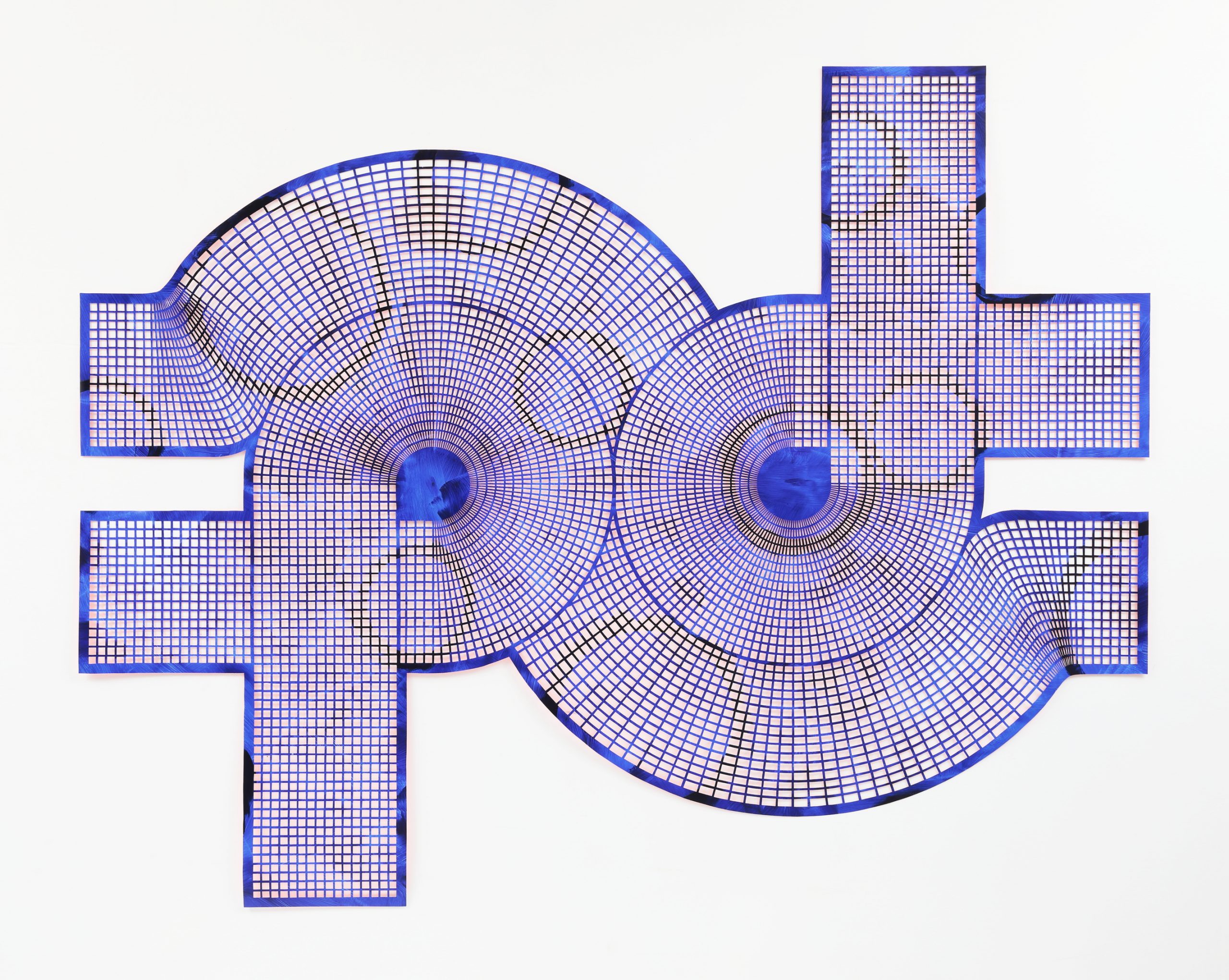

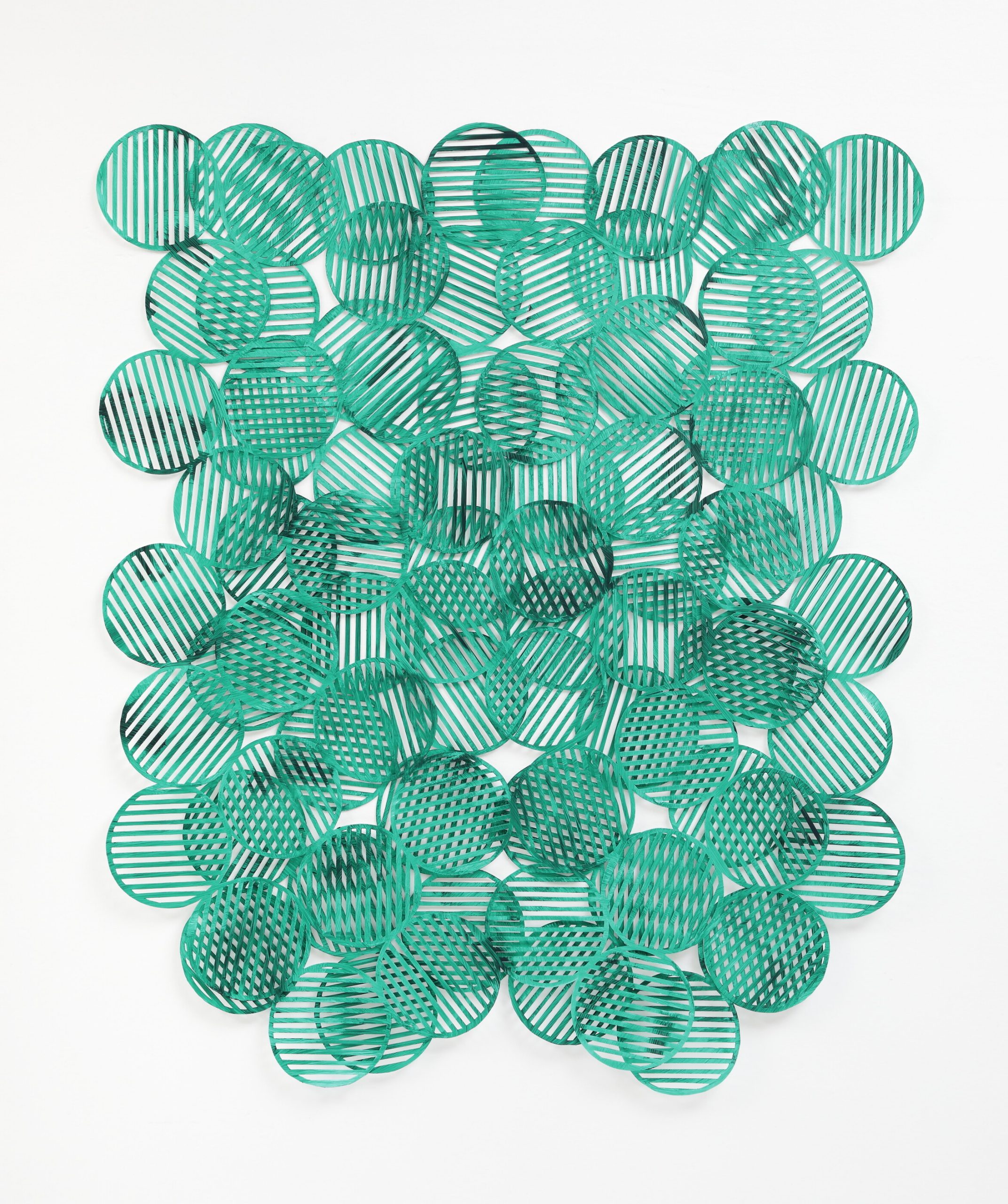

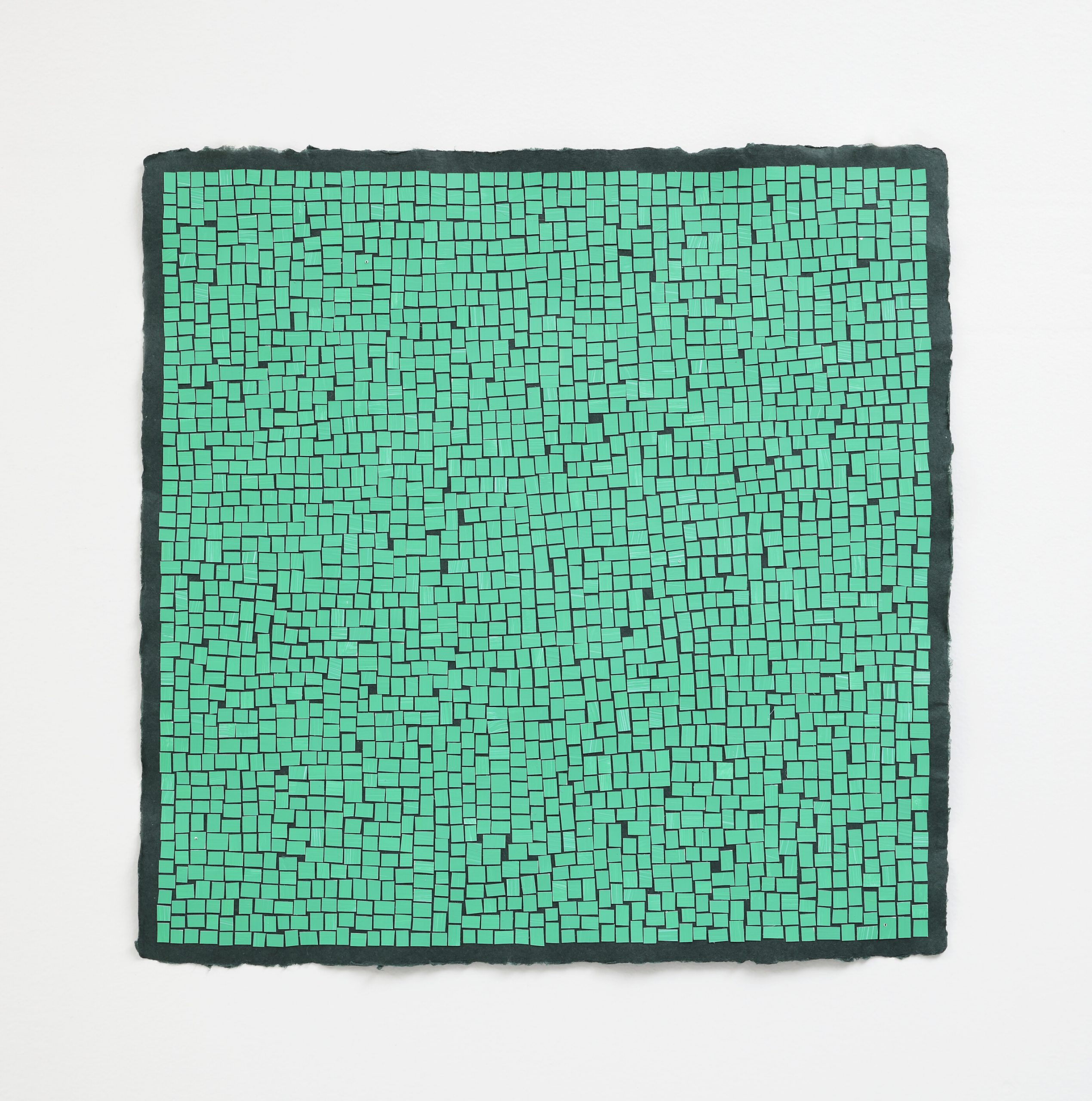

Carolyn Case’s work is unapologetically painterly, with velvety surfaces and thick, glossy layers of oil paint which seem to emerge almost three-dimensionally from her panels. Carolyn presented these new paintings and a series of richly-hued pastels on paper in her current exhibition, "Test Kitchen," which is on view at the gallery through May 8th.

"Test Kitchen" is the Baltimore artist’s first solo show with Reynolds; it serves not only a strong culmination of the work she created over the past year, but also as a humbling experience for Carolyn and her practice. We can visibly see how she “figures out” concepts and ideas in her recent pieces by building up and scraping off surfaces, interconnecting imagery from her home life and the outside world. In the interview below, we speak with Carolyn about how this deep connection—and sometimes, struggle—with her work and the balance of life play out in her compositions.

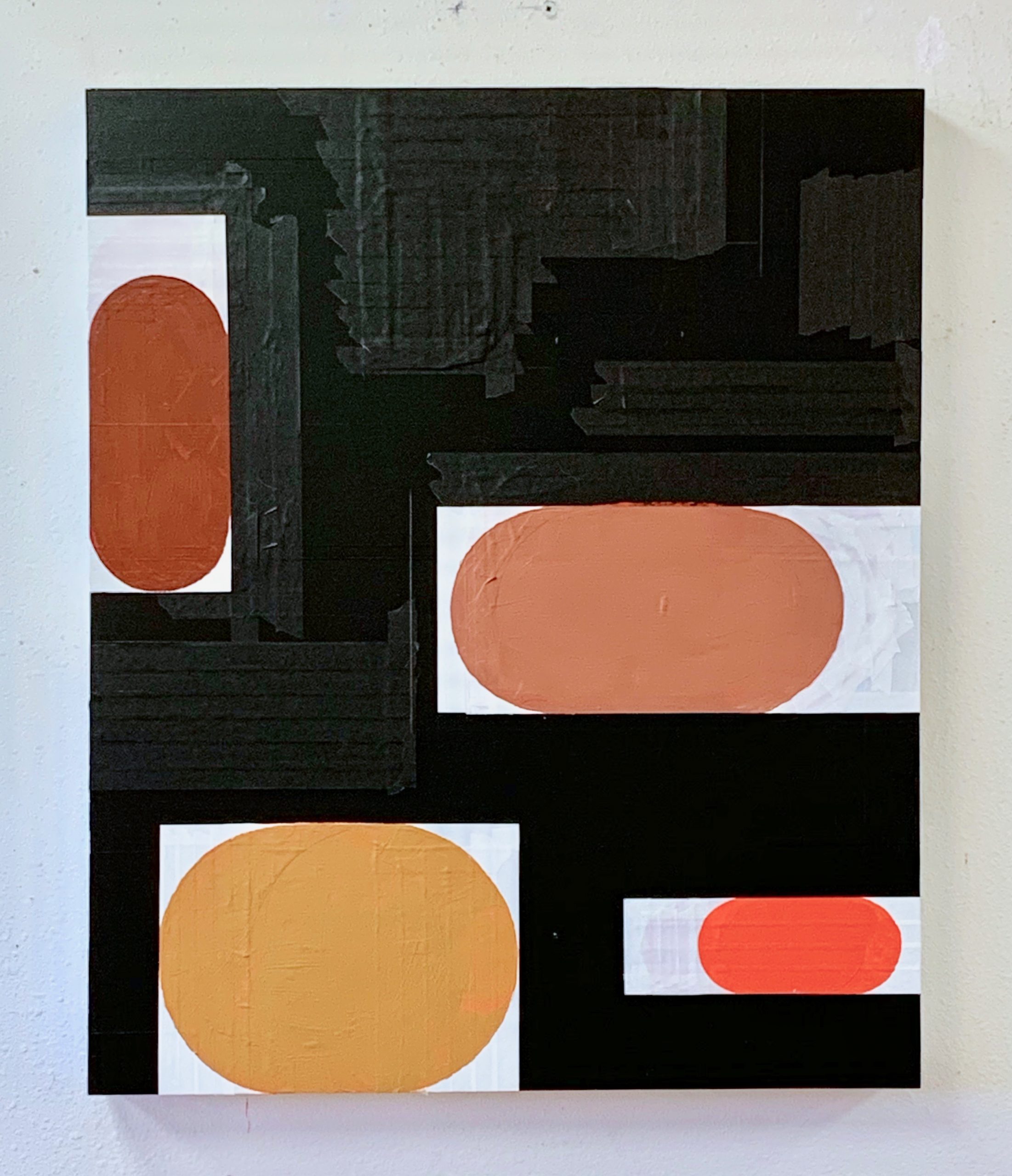

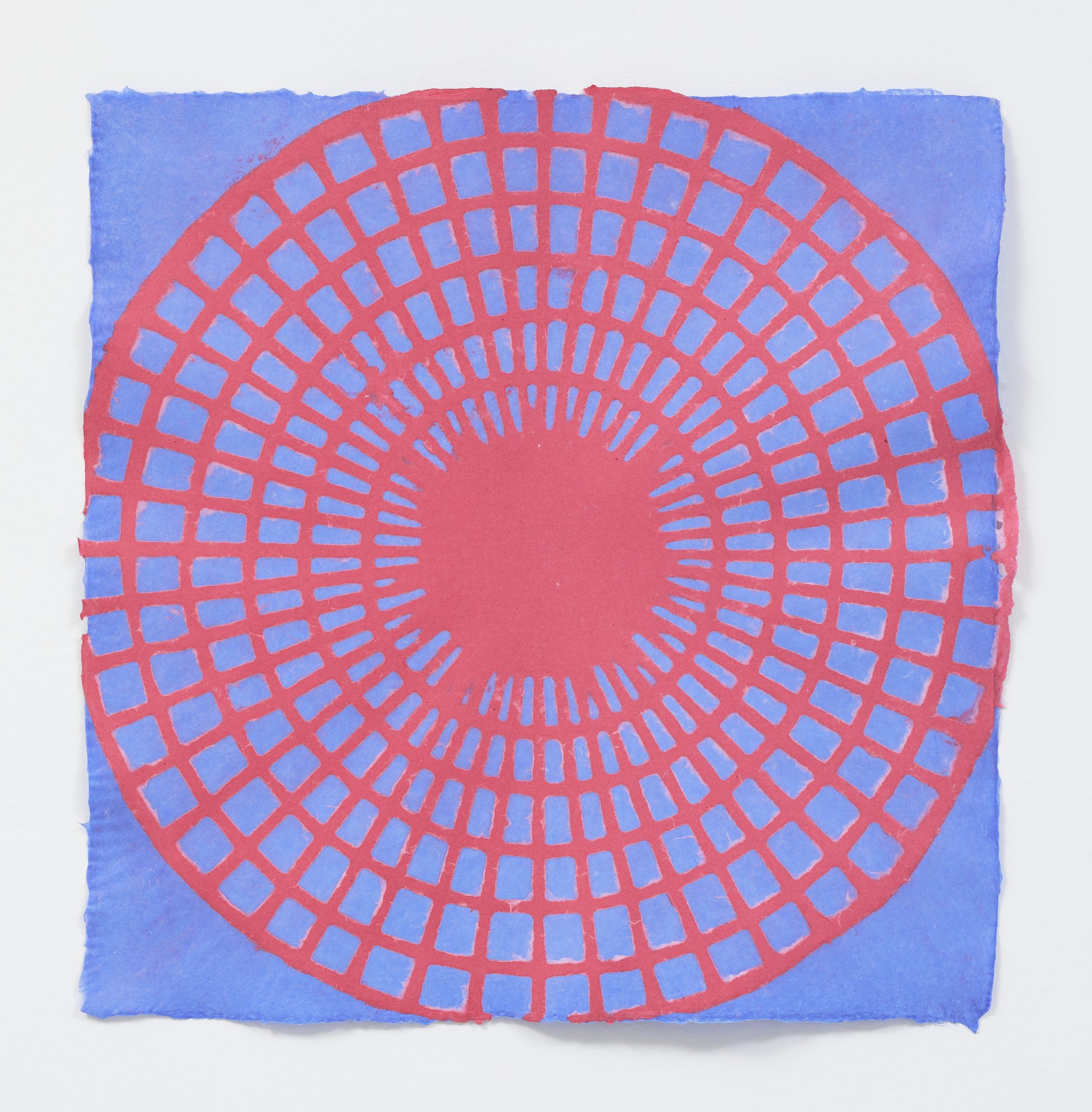

"Red Sink" - one of the paintings currently on view in Case's exhibition "Test Kitchen"

When did you first start painting? Did you always know you wanted to be an artist?

I originally wanted to be a graphic designer after being editor of my yearbook. However, as soon as I took drawing I in college, I knew I would be an artist. Unexposed to art classes in high school, I didn't take drawing or painting, but I always made my clothes, jewelry, and furniture. So, I think I was always compelled to be creating.

Have you always worked in the 2D field?

Yes, I have always painted or drawn, but recently I have been experimenting with ceramics and casting. I have also signed up to learn glass fusing this summer. I want to make my frames for the pastels, so that is a goal for the future.

What is a typical day for you in the studio?

I usually work about 6-7 hours three days a week, and then I like to work a couple of hours on Saturday and Sunday. I have arranged my teaching schedule to be stacked on Monday and Tuesday to get the most uninterrupted time in the studio. I am usually working on several things at once, but I'll often get hooked into one particular piece as the image starts to appear. I don't have pre-planned outcomes for my paintings, so there's a lot of trial and error and discovery in the process.

In addition to being a practicing artist, you're also a professor at Maryland Institute College of Art and a mother of two boys. How do you balance your studio time with everything else? Has this ebb and flow made its way into your paintings?

This question is the most challenging part of my practice! It has been tough to balance, especially during the pandemic with everyone in the house. I try to accept that I won't be able to go at the pace I would like, and my children growing up reminds me that this is a short period in my life. I don't think there is a way to balance it truly; it's more accepting that things will be out of balance. With MICA, working with the students and being around artists pushes me forward; overall, I have to be careful with how much I volunteer.

Your new body of work draws from your life at home, specifically in the kitchen and during COVID - can you tell us more about this and how this inspiration differs from or relates to previous work?

My other work was more landscape-inspired, and after I had children traveling slowed down, and taking care of feeding everyone ramped up. The kitchen became my second studio and creative space, it had interesting tools, and I was able to experiment and travel through cuisines. It was also a chore and a burden, so I had to find ways to make it a creative space to stay connected to my studio practice. I think a lot of my subject matter is trying to keep a creative outlook and finding the magic in life throughout my day. Life is mysterious, and I want to keep a curious mind.

What kind of imagery can we identify in your paintings and pastels? What is left ambiguous?

I am very interested in kitchen tools - spatulas, pots, burner coils, oven mitts - so that makes up a lot of the shapes and imagery you see. I also have photographs of my terribly dirty sink with the remnants of cooking: spaghetti noodles and bits of lettuce floating in murky water.

You paint with such intention - your work is bold, thick, and rich. What does this texture do to your paintings? How is this texture and process communicated differently in your pastels?

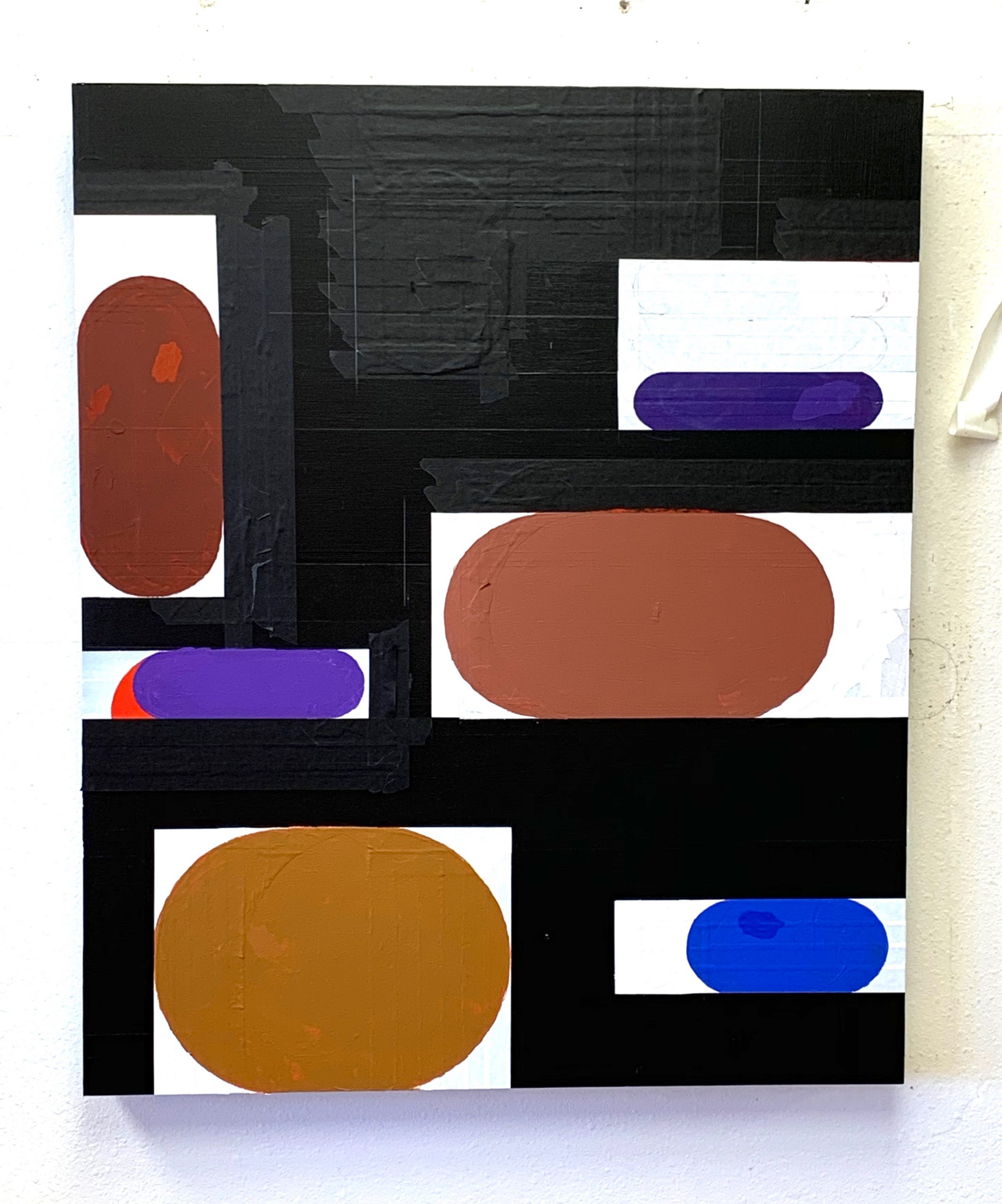

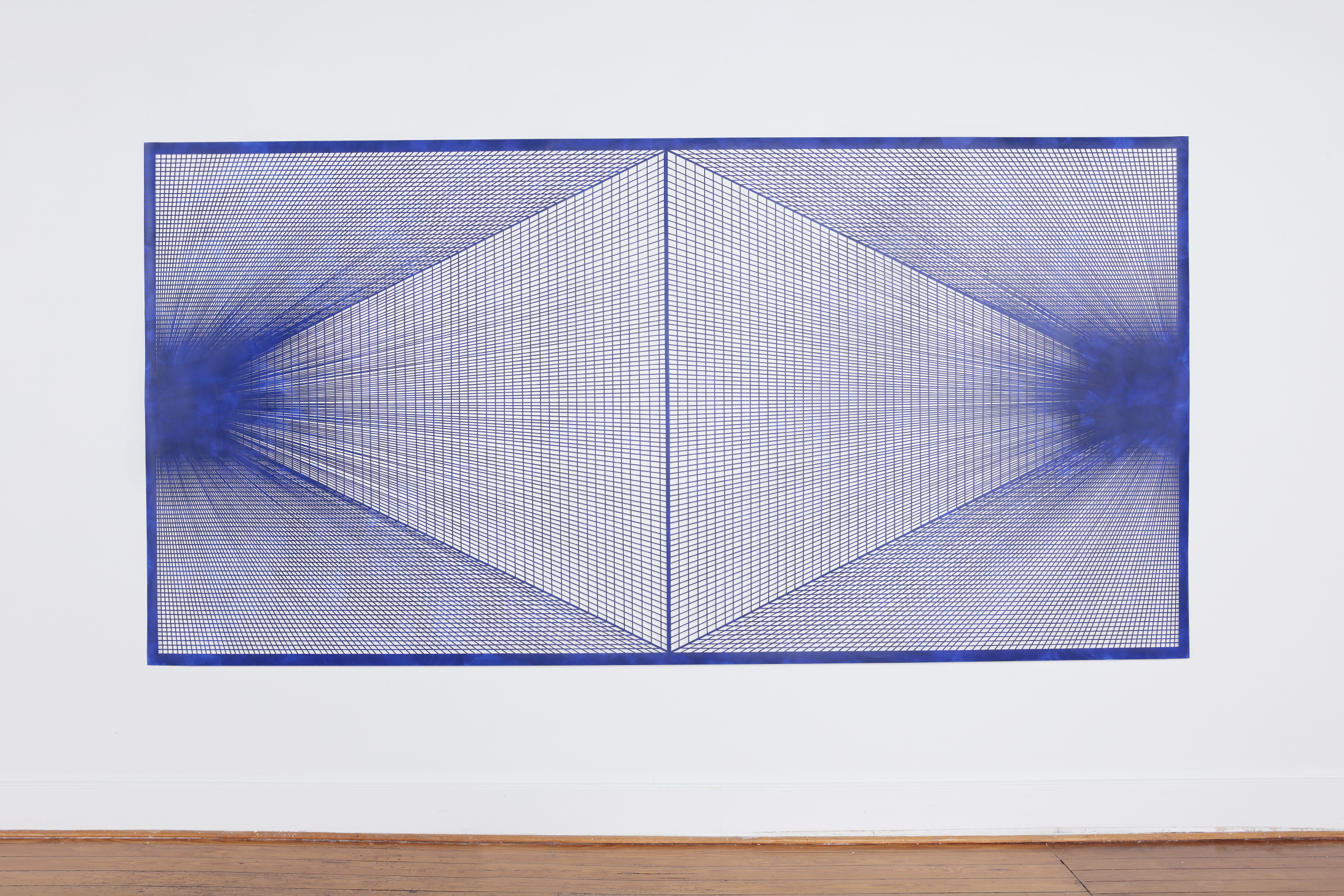

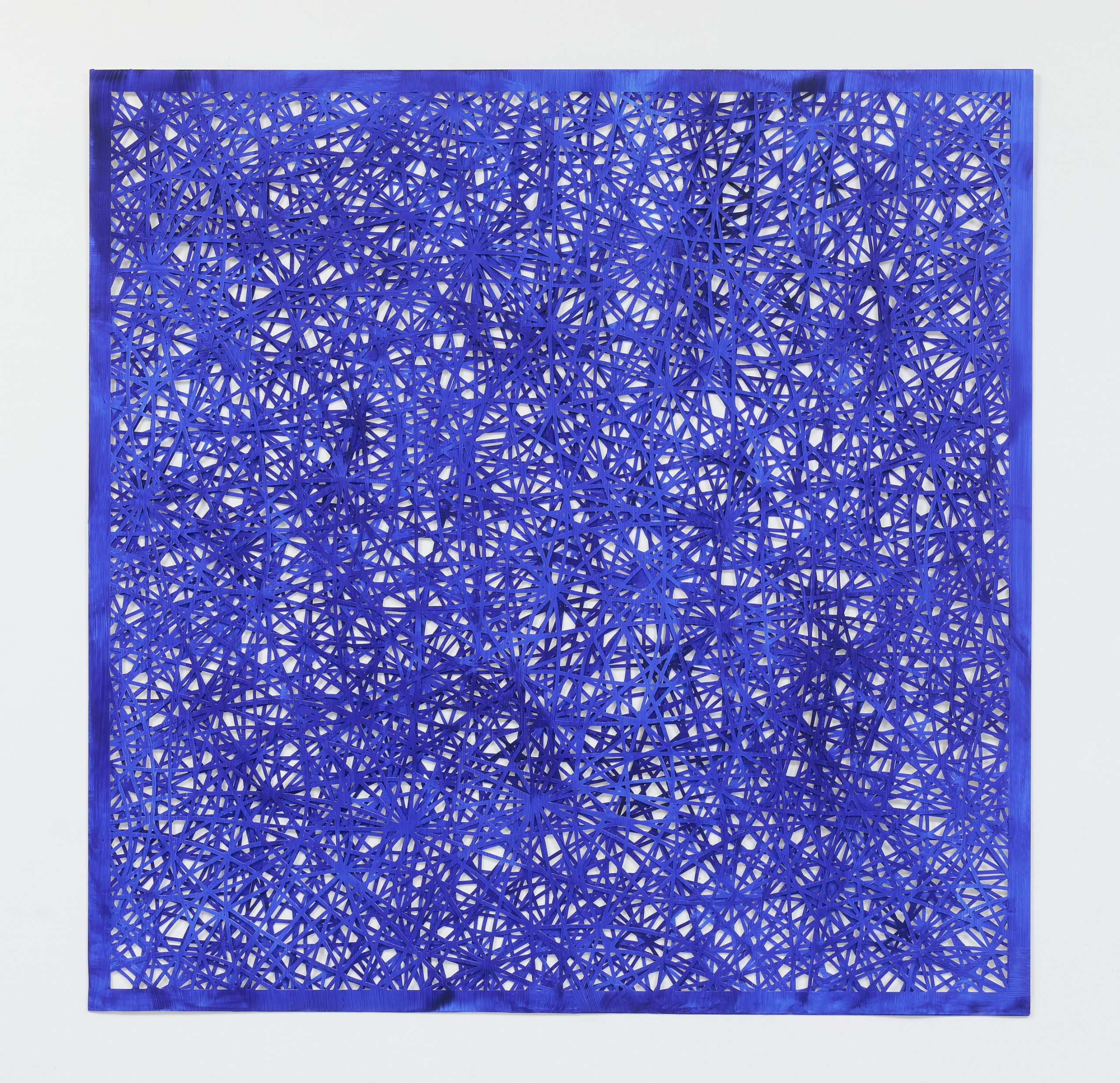

Installation image of "Test Kitchen"

My older paintings had a sort of very refined surface because I was sanding down and repainting every decision. As I was developing this new imagery, the process became more spontaneous, and I just decided to let every idea get painted right on top. This way of working changed the surface dramatically, and at first, I didn't like it. But then I thought of it as my own body and life experience - how you build up wrinkles, scars, and imperfections as you live life, and there is a vulnerability and acknowledgment of life by allowing it to show.

The pastels are very direct. I usually have an idea and stick to it (for the most part). I use the pastels to deepen and iterate on an idea. Also, I use a special pastel paper to build up layers quickly, and the surface stays very uniform.

What does color mean to you in your process? What kind of color relationships interest you? Any specific inspiration we should know about?

I love color! I immerse myself in it. My color decisions are usually intuitive, and then I react to whatever spontaneous decisions I have made to create space. I love melting chaotic space, so I want the color choices to help organize that spatial sense.

What's next for you? Your work? What are you excited about?

I am very excited about a grant I received to do glass fusing this summer. I also received enough money to buy a glass kiln. I am still working on creating handmade frames for the pastels, so I hope to incorporate the glass fusing.

Case received her Bachelor of Fine Arts from California State University and Master of Fine Arts from Maryland Institute, College of Art (1994, 1997). She currently lives in Baltimore where she has been a professor in painting and drawing at the Maryland Institute College of Art since 2011. She is the recipient of fellowships from the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, the Maryland Institute of Art and Vermont Studio Center, as well as a residency from the Kanoria Art Center in Ahmedabad, India. She has exhibited at the Katzen Art Center, the Corcoran Gallery, Hemphill Fine Arts in Washington, DC and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, California.